Hi everyone and happy Thursday!

Thanks again to everyone who participated in our first Technical Alpha and gave us feedback. Now that it’s been a few weeks, we’ve had time to absorb your responses and make changes we think you’ll really like. Before we get into the weeds of what’s new, let’s shed some light on how we developed the systems in the game, and how we’ll continue to iterate on them.

Here at Oxide there’s a pretty healthy love for all things board game – we have regular after work game nights, lunchtime sessions, Magic: the Gathering draft tournaments, and multiple bookcases full of games both recent and decades old. You’ll find people as eager to join in on a quick session of Innovation to investing sixteen hours into a single game of Twilight Imperium. Yes, it lasted that long. No, it didn’t need to last that long. I’m not bitter.

Board games run deep through the veins of the company, and some employees have even published and worked in board games professionally at different stages of their career, from Space Hulk to pen and paper RPGs to Avalon Hill titles. If you’ve ever been over to the Career page on the website, you’ll also see that in most game design postings, we list experience in board game design as a plus.

This might seem a bit odd to some, but in the end, mechanics in the kinds of games we make share a lot of DNA with board games, particularly strategy and eurogames. How an analog game has approached a mechanic and system can be a good source of research for similar mechanics in the digital space.

Extending that a step further, we’ve even prototyped mechanics for our digital products as a board game first, not only because it can be faster to get something up and playable, but there’s also nothing to hide behind. There’re no flashing graphics or pretty visuals, no swelling soundtrack or helpful UI panels to guide you through a difficult flow. It’s just you and the mechanic. And if the mechanic sucks, boy do you find out fast. It sucks hard.

Taking your ideas frst to paper isn’t revolutionary, and other industries even have a word for this – paper prototyping. It’s exponentially faster and cheaper to write up some old index cards with some colored markers and throw those in the trash and write up a few more, than spend the time architecting a new system for 3 weeks only to find that maybe it’s just not such a good idea in the first place. Index cards are cheap, buy them by the hundreds. Want to be more environmentally friendly? Raid the recycled paper box at your office/school and use the backs.

Figure 1: Paper Prototype from the office. It’s fancy, it’s got *colored* index cards

Not every mechanic can translate directly to an analog version of itself easily, and that’s ok too. But by attempting to simplify what you have, put it down to paper, and then most importantly, TESTING IT, you’re accomplishing a world of things faster than if you spent weeks documenting and weeks waiting for code support. Don’t waste that time, play and test your ideas. Trash the bad ones, iterate on the ones worth saving. Play and test again.

So when it comes to students graduating college and juniors looking to expand their skill set and portfolio, I can only loudly suggest all the more the importance and power of trying your hand at some paper board game designs. Don’t worry if they’ll suck. They will. The first ones always do. But that’s what learning is all about – failing and learning from that failure. Figuring out what you can improve and then acting upon that new information is actually how you grow and learn and get better at doing anything. If you’re spending 8 months developing a game in an off-the-shelf engine all by yourself, you’re not iterating fast enough. You’re not failing fast enough. In that amount of time you could have made literally like 40 different board games, allotting yourself one game a week. It’s definitely doable. Insane perhaps, but you’ll get in the rhythm. And even if only 15% of those are worth taking further and finishing, that’s still quite a few finished games in your portfolio. Put them up as print-2-plays, or using something like The Game Crafter sell them on a marketplace, or take your favorite one and then move that to your engine and spend time perfecting it as a video game.

Figure 2: Random article, your best friend

Don’t have ideas? Just use some random idea generators or the “Random Article” on Wikipedia and make a game out of what it spits out. Some of these will be terrible, but they’ll force you to start thinking outside the box and start designing within constraints. Practice, practice, practice.

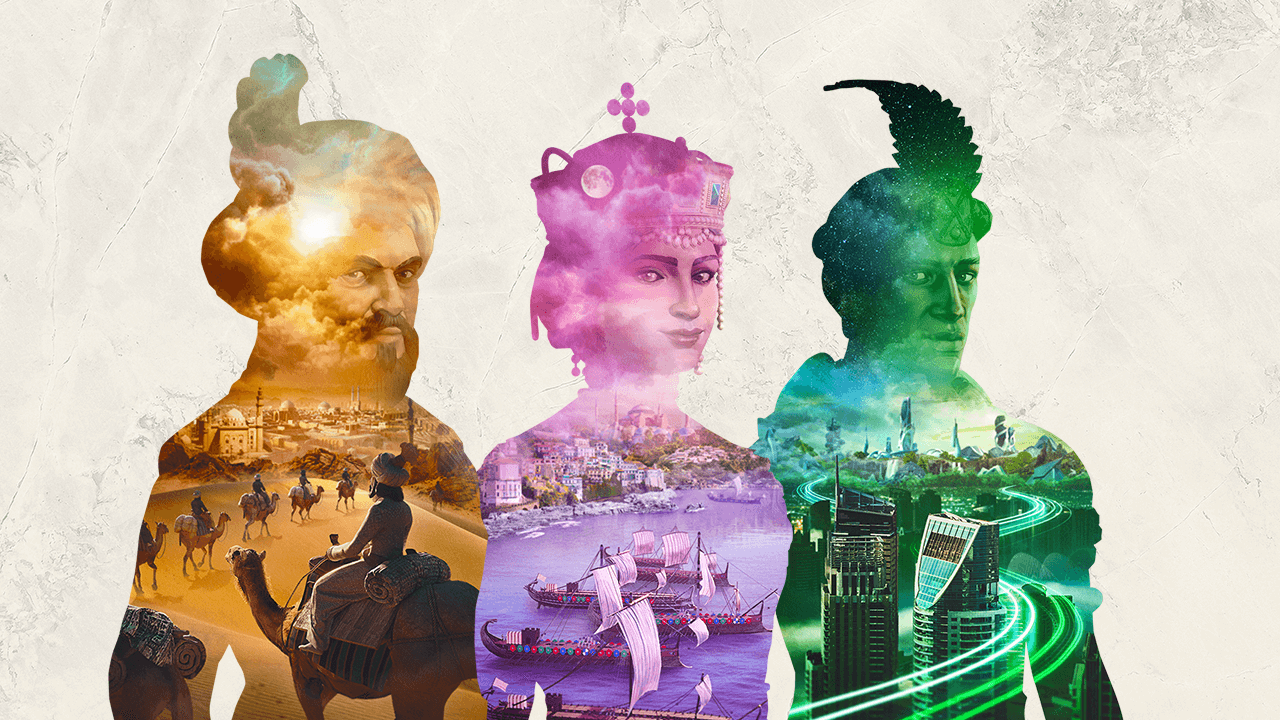

The more you actually design and play and test and design again, the better you’ll be in the end at designing in the first place. So go out there and make some terrible games about competitive hotdog eating, a legacy game about the history of paint pigments, a cooperative card drafter on highway repair, or whatever random thing the internet will spit out at you. In the meantime, we hope you continue to be part of our design process as we develop Ara: History Untold.

– The Ara: History Untold Team

Share your thoughts with us on the Insider Forums!